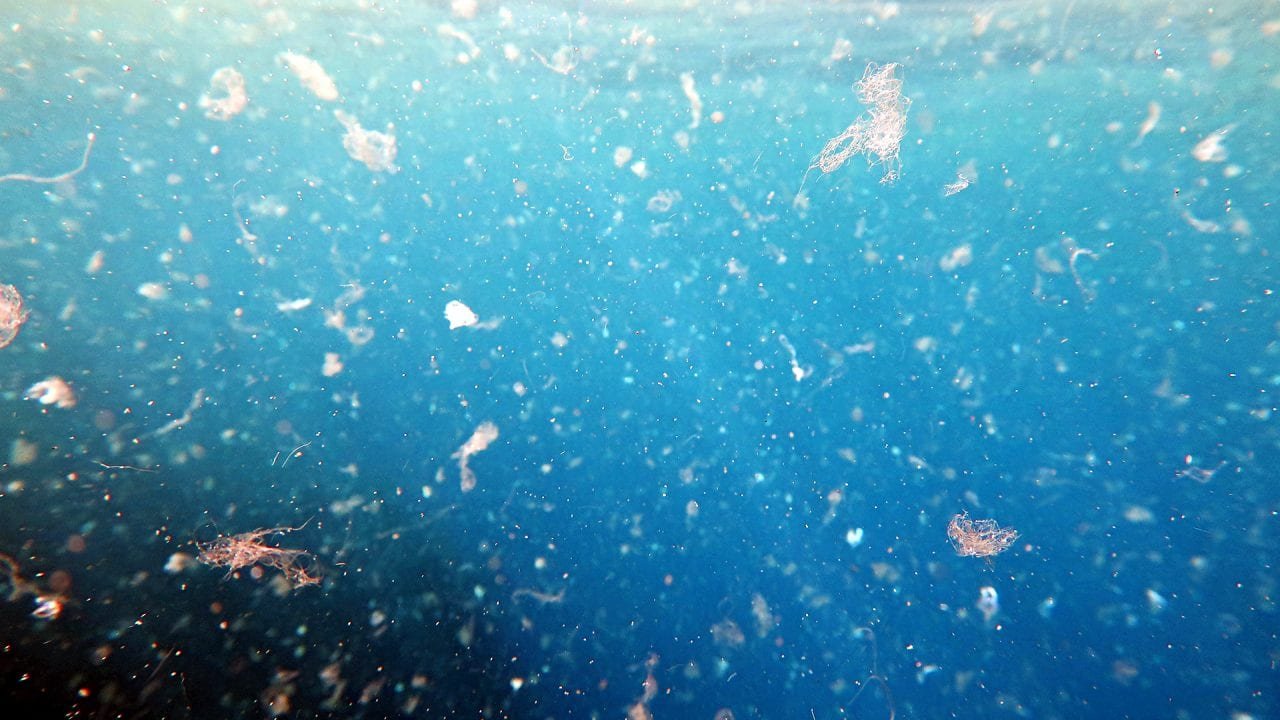

Confetti-sized bits of microplastic get swept through the ocean by fast-moving currents and shifting circulation patterns, creating a snow-globe-like effect. Scientists at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute are investigating where these tiny particles concentrate in the global ocean to identify microplastic “hot spots” and better understand the nature and magnitude of the problem. (Shutterstock)

In the Ocean, It’s Snowing Microplastics

Tiny bits of plastic have infiltrated the deep sea’s main food source and could alter the ocean’s role in one of Earth’s ancient cooling processes, scientists say.

Although the term may suggest wintry whites, marine snow is mostly brownish or grayish, comprising mostly dead things. For eons, the debris has contained the same things — flecks from plant and animal carcasses, feces, mucus, dust, microbes, viruses — and transported the ocean’s carbon to be stored on the seafloor. Increasingly, however, marine snowfall is being infiltrated by microplastics: fibers and fragments of polyamide, polyethylene and polyethylene terephthalate. And this fauxfall appears to be altering our planet’s ancient cooling process.

Microplastics now contaminate the entire planet, from the summit of Mount Everest to the deepest oceans. Photograph: David Kelly

It’s in our blood

Meanwhile, much closer to home, no matter where you live, microplastic pollution has been detected in human blood for the first time, with scientists finding the tiny particles in almost 80 percent of the people tested. The discovery shows the particles can travel around the body and may lodge in organs. The impact on health is as yet unknown. But researchers are concerned as microplastics cause damage to human cells in the laboratory and air pollution particles are already known to enter the body and cause millions of early deaths a year.

World starts to hammer out first global treaty on plastic pollution

Each year, an estimated 11 million tons of plastic waste enter the ocean, equivalent to a cargo ship’s worth every day. The rising tide—in the oceans and beyond—is just a symptom of much wider problems: unsustainable product design, short-sighted consumption, and insufficient waste management, scientists say. To curb the flood, says Jenna Jambeck, an environmental engineer at the University of Georgia, “we need to take more action and it needs to be further upstream” in the production process.

That’s exactly what negotiators from 193 countries are setting out to do when they meet in Nairobi, Kenya, next week. Their ambitious goal: to create a negotiating committee that will try to hammer out, within 2 years, a new global treaty intended to curb plastic pollution.