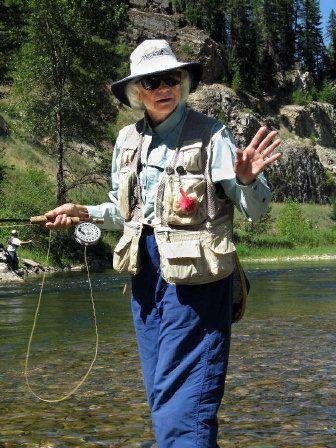

Justice O'Connor pauses while fly fishing on Idaho's St. Joe River on July 19, 2005 (Rich Landers, The Spokesman-Review)

Justice Sandra Day O’Connor (1930-2023) was a trailblazer in America’s legal field and she was an passionate fly fisher.

Spokane reporter Rich Landers spent a day fishing with the Supreme Court justice in 2005 and year’s later wrote the following remembrance (published in The Spokesman-Review, on October. 24, 2018).

A newspaper writer is more likely to get a hug from President Trump than a day on a trout stream with an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court.

I cherish that day – July 19, 2005 – more than ever this week as Sandra Day O’Connor, 88, has announced she is retreating from public life.

While St. Joe River cutthroats turned their spotted backs on us, she taught me lessons in law, leadership and grace during one of the most memorable days of work in my 40-year career as outdoors editor for The Spokesman-Review.

O’Connor was in Spokane to deliver the keynote for the 9th Circuit Judicial Conference. Organizers asked me if I would help satisfy her passion for fly-fishing in the morning and afternoon before she spoke. I was vetted by U.S. Marshals a month in advance. I even broke the angler’s code and gave them directions to my favorite fishing holes.

A week before arriving, O’Connor called from Washington, D.C., to work out details. In that conversation, the justice famous for being the court’s swing vote confirmed her definitive position on “Row” v. Wade.

“I don’t want to be confined in some little boat when you can have a whole river around you,” she said. “I sit on my butt enough. I want to wade.”

I loaded her into my minivan by the Davenport Hotel at 7 a.m. She was perfectly equipped for the court of piscatorial opinion – felt wading shoes, quick-dry wet-wading pants, a 5-weight travel rod and a Hardy Princess reel.

“I love to golf,” she said. “But you can golf almost anywhere. It’s not everyplace that you can go fly fishing for trout.”

She also brought her husband, John, who was in the advancing stages of Alzheimer’s. Caring for him was the main factor in her decision to announce that she would retire 24 years after then-President Ronald Reagan had appointed her to be the first woman on the Supreme Court.

I was her host for a day of fishing, and out of respect I never took out a recorder or notebook to copy down a quote. But in preparation for “my Sandra day,” I had read her books and numerous stories about her.

I’m no stranger to strong women. My wife is among the female physicians who broke trail through male-dominated institutions for the legions of women who have followed their footsteps.

O’Connor was in a league of her own – laser sharp, politically masterful, yet as down-to-earth as the Arizona ranch girl who used to plink jackrabbits with her .22.

At the age of 20, she graduated from Stanford University and then completed Stanford Law School just two years later, ranking third in her class, behind valedictorian William Rehnquist, who would later become chief justice of the Supreme Court.

Yet more than 40 law firms rejected her requests for interviews to work as an attorney – because she was a woman, better suited to be, say, an office administrator. She bucked the flow to peak out as one of the most respected jurists in the world.

Federal court Judge Robert Whaley of Spokane was in the minivan with us that day and the conversations traveling to and from the river covered a number of her toughest decisions, such as when to give up on a dry fly and resort to a beadhead nymph.

She enjoyed seeing Lake Coeur d’Alene and being reminded of her role in a Supreme Court decision involving tribal jurisdiction.

Then she asked me to stop on the side of the road near St. Maries so she could jump out and snap a photo of a flock of wild turkeys.

She was vigorous in her defense of an independent judiciary, galled by Congress’ attempt to override states’ rights in the Terry Schiavo case and saddened by the trend in Congress – even then – to define judges as “activists” for decisions based on the law.

How did she recommend dealing with these adversaries?

“I try to be friendly with them,” she said. “We all learn more that way.”

With knowledge of history and vision of the future – sealing her reputation as a jurist rather than an ideologue – she made a point in one conversation to emphasize that Supreme Court decisions should interpret the Constitution in tiny ticks.

The court routinely makes narrow rulings that disappoint people seeking sweeping changes in the law, she said. “It’s not our role to swing with the pendulum of political climate,” she said. “That would be a path to anarchy.”

She also confirmed that a judge from the highest court in the land could fish a river named “St. Joe” without compromising her position on the separation of church and state.

And she didn’t need her U.S. Marshal escorts. She gave them the day off so she and her husband could enjoy the outdoors much as normal people would. She had me stop in St. Maries so she could buy a bag of beef jerky.

The North Idaho forest was gleaming green that day, the skies blue and cloudless and she loved the cool water on her legs as the daytime temperature soared toward the 90s.

The river’s cutthroat trout, famous for being agreeable to virtually any offering, refused almost every fly pattern O’Connor, Whaley and I drifted down the stream.

“We’re doing everything we can, but it would help if the fish were a little more cooperative,” I said.

“Yes, it’s like the Congress,” she answered with a grin.

For the record, she caught no fish that day. She graciously noted that she also got skunked while fishing in Montana on Tom Brokaw’s private stretch of the West Boulder River.

Had we not had to leave the St. Joe at 4 p.m. to be back in Spokane for her talk, O’Connor likely would have caught and released dozens of trout.

“Look, the bugs are hatching as the sun gets lower and cutthroats are coming to the surface,” I said pointing to the rise rings in the water as we retreated.

“Duty rules again,” she said. “It’s the story of my life.”

During the return drive, the discussion drifted from fishing stories back to the Supreme Court and women in high places, or the lack thereof. O’Connor pointed out that more than 50% of the students in U.S. law schools were female, yet by 2005 there was only one other woman, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who had ever served on the Supreme Court.

“That’s not acceptable,” she said – that was about 15 minutes before my mobile phone rang with a call from The Spokesman-Review office.

While we’d been fishing, President George Bush had announced his nomination of John Roberts to be her replacement on the court.

The editor on the phone asked me to give the news to O’Connor.

Her first words were unequivocal: “That’s fabulous!” she said. She immediately described Roberts as a “brilliant legal mind, a straight shooter, articulate, and he should not have trouble being confirmed by October. He’s good in every way, except he’s not a woman.”

The Spokesman-Review was the only media outlet with access to a Supreme Court justice in that important moment. We published that reaction, and the quote was picked up around the world.

My phone rang incessantly the next day, mostly with calls from media as I drove with my wife for a hiking trip at Mount Rainier.

I didn’t tell reporters and talk show hosts all that I’ve told you in this column 13 years later. That morning the paper published my story about a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity that had eluded the Washington press corps. Beyond what I’d written, my fishing buddies and I left everything else on the river.

O’Connor showed her mettle that day, climbing several slick, steep riverbanks without so much as a dissenting opinion.

I most fondly remember and cherish her holding my hand as we waded waist deep in the flowing St. Joe to cast her fly.

“I’m used to bucking the stream,” she said.